We pay respect to traditional owners and the wider community. Be mindful that this story includes names of deceased people. Please show respect and be careful.

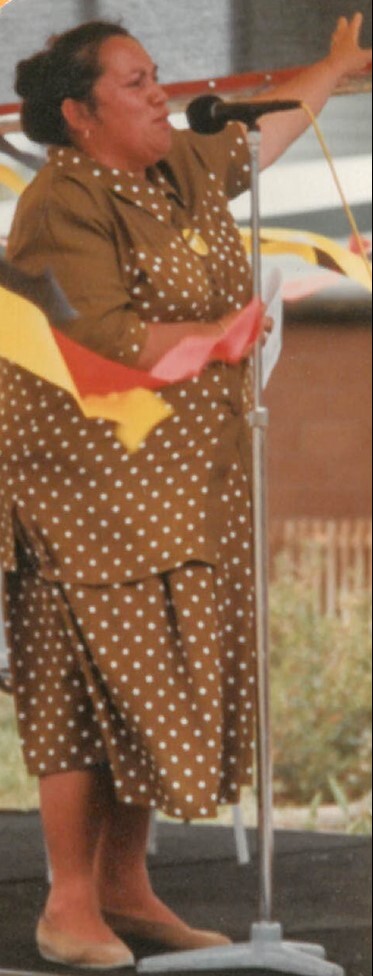

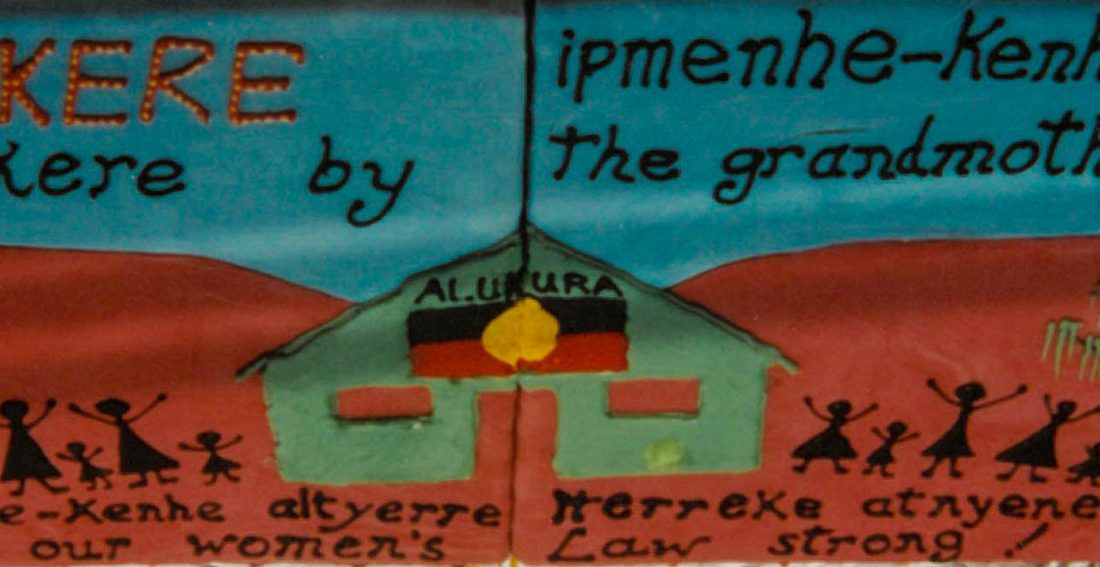

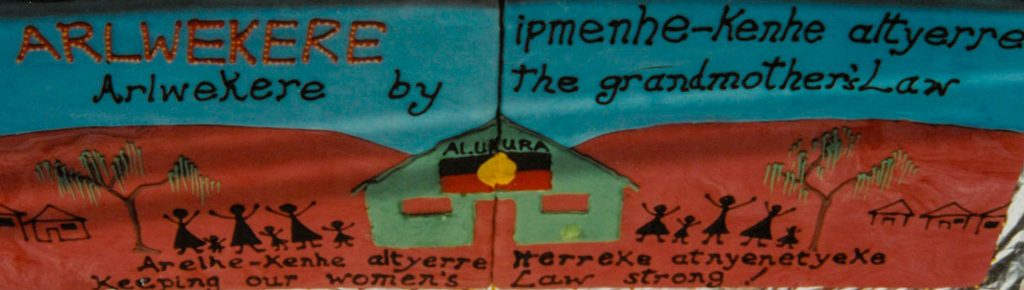

On this day, 27th October 1994 (27 years ago), the Alukura building in Percy Court was officially opened. The photo shows the big cake that fed 400 people at the opening ceremony. On the cake, Alukura is written as Arlwekere, in central and eastern Arrernte language. Alukura is the name of the Women’s Health Service run by Congress. But the name Alukura doesn’t belong to Congress. The name refers to women’s law and is Aboriginal cultural property.

The struggle for Alukura took many years. Helen Liddle has shared memories of one key part of this struggle, when she and other Aboriginal women spoke up at the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) international conference on Healthy Public Policy in Adelaide, in April 1988.

Helen remembers: “In 1988 Congress was in a continuous battle with NT Health over getting Alukura funded. Congress had been told lots of stories by Federal government people about funding for Alukura but there was no action. I was Deputy Director (CEO) of Congress at the time and it seemed to me that the WHO conference coming up in Adelaide was an important opportunity to embarrass government about the lack of action.

The problem with this idea was that 1988 was the bicentennial year and the WHO conference was a bicentennial event. Nationally, Indigenous organisations had made a conscious decision not to be involved in bicentennial events. But other Aboriginal people I consulted agreed it was a key opportunity for getting support and were OK with me going.

I made a plan to go to Adelaide with two other women, Mantatjara Wilson and Helen Morris. Mantatjara, from Mutitjulu, had been strong right the way through the consultation process about Alukura. Helen was a health worker, a Warlpiri woman, who used to work with Pip Duncan doing the women’s health checks at Congress Hartley Street clinic.

On the day we were flying to Adelaide we hit another problem. There’d been major rain in Alice Springs. The Gap was closed by flooding. Cars could not get through. But the airline sent a 4WD bus to get people to the airport and eventually the plane was able to take off.

At the conference ours was the only Indigenous presentation from Australia and we were the only Indigenous people from Australia, because of the boycott. We got a few other women to come in support of us: my friend Ruby Hammond came and Marjorie Tripp who worked for Aboriginal Affairs Department, and a few others, about 6 to 8 women all up.

Our presentation was early in the conference. The room was small but about 200 people came to listen; it was bumper to bumper through the whole room and out the door! The international audience was very interested and they wanted to know why they hadn’t heard about the Alukura proposal before. Later people came up to us and were sorry they had missed our presentation so we did extra presentations all through the conference week. It was amazing. We had wanted to tell the world that we had this great idea and we were received with open arms!

In the closing plenary all the WHO directors were going to be on stage and the Australian Minister for Community Services and Health, Neal Blewett, was going to speak. We’d had advice from a support group that formed to help us. They told us to sit in the very front row and wait until they gave us a signal that the time was right.

Neal Blewett talked for an hour on the state of health in Australia. In all that time he mentioned Indigenous health just once. He acknowledged Indigenous health was terrible, but he just made that one short mention.

When he finished talking, we got the signal. I got up on the stage and helped the others up. We’d been warned that the WHO head would switch off our microphone which would mean no one in the conference would hear our words. But I said to the head of WHO “Don’t switch us off. Can we just say a few words?” The WHO head checked with Neal Blewett and he said ‘OK’.

After I spoke, Neal Blewett said he had known nothing about Alukura. Later he met with us privately. He said he could not understand why he had not heard about the Alukura proposal. I told him “We’ve been talking to public servants about it; the talks have just been going around and around, going nowhere.”

The Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Gerry Hand rang me very soon afterwards. He asked me “What the f*** did you do that for, Helen?” referring to the way we had embarrassed Neal Blewett internationally. He asked me for the Alukura proposal documents and said “You will have your funding for Alukura. You can make an announcement now, before the end of the conference, that you have got the funding.”

The women’s strong action at the conference was a breakthrough in the struggle to fund Alukura. Just a month later, in May 1988, Alukura was able to move into its own premises, 14 Mueller Street. Aboriginal Hostels Ltd, who owned that building, had offered it to Congress so the women’s health clinic could be in a separate women’s space to the main Congress clinic in Hartley Street. Funding for Alukura Percy Court building was secured in 1991, the building was completed in 1992, the first baby was born there on 30 September 1993, and the official opening followed on 27 October 1994.

Cake for 400 people made for the official opening of Alukura building in Percy Court. The design by Alice Springs artist, the late Pam Lofts. It shows the building that Alukura used from May 1988 to December 1992, which was on the corner of Mueller St and Sturt Terrace in Eastside.

The plaque was unveiled at the Alukura opening.